Nashville Disasters: A 150-Year History of Helping Others

by David Steele Ewing

Style Blue Print

While most people think 2020 tested Nashville like we have never seen before, our city has faced many disasters dating back to the 19th century. With each one, neighbor has helped neighbor, citizen has helped stranger, and many gave their time and money, and saved lives as the water rose, flames burned hot, trains crashed, tornadoes ripped apart neighborhoods and buildings, and pandemics spread. Nashville has been strong long before a hashtag campaign was created — because its residents immediately dropped everything to help others in need.

Here’s a look at the Nashville disasters and transformative events that shaped Nashville from 100(ish) years ago into who we are today.

Nashville Disasters: A 150-Year History of Helping Others

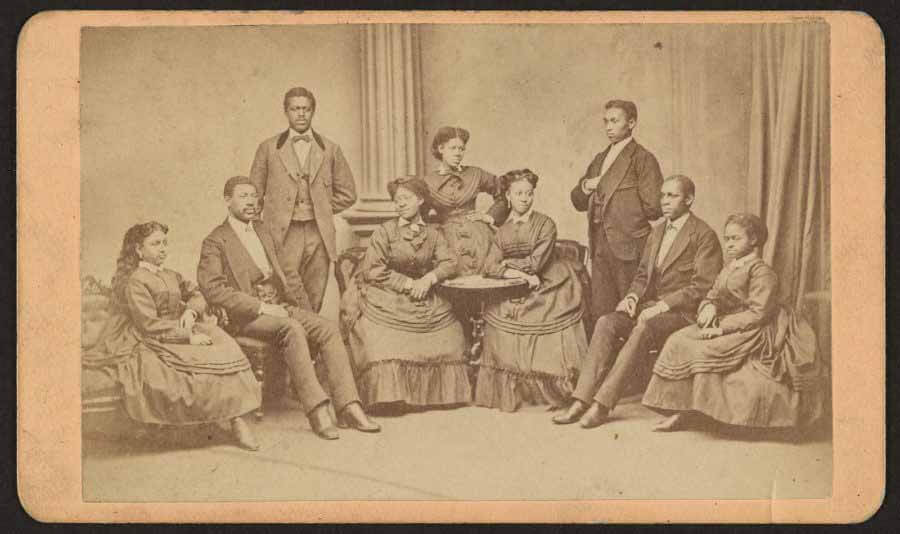

1871: Fisk Jubilee Singers Help Chicago Fire Victims

While Nashvillians notoriously care for their own, they also have been generous to people living outside the city. On October 8, 1871, the Fisk Jubilee Singers were on their first tour across America as an unknown group with little money, trying to raise funds to support their new college. During its early days — outside of Nashville newspapers — the fledgling group did not get much attention in the press. They needed to raise money on this tour to pay for their travel and to keep the doors of Fisk open. Every dollar was needed for the school.

After a concert in Cincinnati, OH, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 that killed more than 250 people and burned three-and-a-half square miles of the city was still on everyone’s mind. The young singers saw an opportunity to help Chicago, and the whole group agreed on what to do with the proceeds from their concert that night. Maggie Porter, an original member of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, later recalled their gift to the Chicago Fire Fund: “We had $30 and sent every penny to Chicago and didn’t have anything for ourselves.”

This act of generosity was noticed by many, and newspapers started to write about these singing students who gave all the money they had to a city they had never visited. With their new attention and positive press, their bookings skyrocketed and their act of kindness came back to them tenfold.

Nashville’s Fisk Jubilee Singers (pictured) gave all of their proceeds from one of their early concerts to victims of the Great Chicago Fire. Image: Library of Congress

1882: Fannie Battle Helps Flood Victims

Nashville has seen large floods over the years, but one of the most devastating floods happened in January of 1882. Dark rain clouds soaked Nashville, and the unpaved streets were a muddy mess. Rising floodwaters swelled past the banks of the Cumberland River, entered houses and floated away fences and outhouses. Two thousand homes in Edgefield and the Jefferson Street area were badly flooded and underwater. Ten thousand Nashvillians had to flee their homes for shelter on higher ground. Thousands were cast out of work and had no money, food, or place to live.

A public school teacher named Fannie Battle quit her job to work full-time helping those impacted by the flood. Nashvillians were hungry, cold, and needed clothing and shelter. Fannie established the Ladies Relief Society, which raised thousands of dollars, distributed food to those displaced, and gave away $2,000 worth of coal so people could stay warm. In mere days, $5,000 was raised to help those suffering. Others helped, too, like the Noel Mill, which donated extra meals to feed the hungry.

Waiting in a line of 500 people for assistance, one man who Fannie helped said he had “five mouths to feed and not a bite in the house.” Fannie continued this work with her relief organization and pleaded with citizens to support her aid to others year-round. She would later establish the first daycare center in Nashville in 1891 when she noticed mothers who worked in the Nashville mills had no one to look after their children.

Fannie’s name became synonymous with helping out the poor, homeless, widows, and children (just as Father Charles Strobel has now done for decades in Nashville via Room in the Inn). Fannie Battle never returned to the classroom, spending the rest of her life feeding the hungry and raising money for the poor. Her work inspired others to help those in need — even when there was not a disaster.

In 1882, Daily American wrote how united Nashville was in its response to help those in need after the flood. The newspaper wrote, “One proud reflection about the flood is that the humanity of Nashville rises with the tide of misfortune and the brisk energies of our townsmen in the work of relief seconded by the active and substantial aid of all classes of the community.”

When Nashville has a disaster, local citizens immediately and always respond, helping neighbors and strangers.

1912: Reservoir Breach on Eighth Avenue

At midnight on Election Day in 1912 — when Woodrow Wilson won the presidential election — Nashvillians on Eighth Avenue were jolted awake by a thunderous sound as the city’s stone reservoir, high atop a nearby hill, burst, sending 25 million gallons of water down onto the streets below. As the water rushed down in the darkness, washing homes out of their foundations, most people were asleep in bed.

Resident M.T. Hessey, who was in bed with his wife and 4-month-old baby, was awoken by the boom. Before the family could get out of bed, the force of the avalanche of water swept the bed out the front door with the Hessey family still in it. M.T. grabbed an upper part of a tree to safely place his wife and baby as the bed floated downhill; they were later safely reunited.

Nearby, the house of R.M. Lattimer (another Eighth Avenue resident) quickly filled with rising water. He saw his wife floating away and saved her from drowning. Water continued to rise, and fortunately, neighbors broke down their door with an ax to save the family.

Neighbors and families worked together to save one another after Nashville’s Eighth Avenue reservoir broke in the middle of the night in 1912. Image: Tennessee State Library and Archives

1918: Pandemic, Train Crash & World War 1

1918 was the 2020 of its time as three deadly events hit Nashville: a deadly pandemic swept through the city, killing almost 2,000 people, the worst train crash in American history took 101 lives, and hundreds of Nashvillians died fighting in World War I.

The 1918 influenza ravished Nashville. Theaters, churches and restaurants were closed to keep the virus numbers low. The Nashville Health Department said it was easier to prevent the virus from spreading than finding a cure, so they wanted citizens not to congregate. They urged doctors and nurses to wear masks and people to stay home. Despite their best efforts, the city’s hospitals were overwhelmed, and more than 1,000 Nashvillians died in October of 1918.

After the pandemic ended in 1919, a group of Nashvillians believed more healthcare was needed for epidemics and other disasters. A group of Nashvillians including Leslie Cheek, E.B. Craig, R.M. Dudley, L.A. Bowers and John Pitts started Protestant Hospital (which later was purchased by the Tennessee Baptist Convention and became Baptist Hospital and is now known as St. Thomas Midtown) near 20th Avenue and Church Street to provide more healthcare to the city. A nursing school on the campus trained people for the 80-bed hospital.

On July 9, 1918, two trains going 60 miles an hour crashed head-on at a horseshoe bend called Dutchman’s Curve near the site of the current Belle Meade Publix. Killing 101 people and leaving many injured, the mangled crash left people needing immediate medical aid. Hearing the crash miles away, nearby residents ran to the site to offer assistance. The gruesome crash is still the worst train crash in American history. Women who lived nearby rushed to the site with their typewriters and typed letters for survivors to tell their families they were okay. They even mailed the letters for them.

The crash left many of the mainly Black victims unrecognizable. White citizens visited Black funeral homes to assist in identifying people they knew, and the newspaper wrote, “… the color line did not exist in Nashville that day.” Many of these African American victims still were never identified, so Joy’s Florist sent flowers to be placed on the graves of those no one knew.

1926: Christmas Day Flood

On Christmas Day in 1926, Nashvillians woke up to the worst flood in our city’s history. It was 4 feet higher than the 2010 flood, and the response was immediate. Nashville Mayor Hilary Howse, whose furniture store on Third Avenue and Broadway flooded, ordered all city vehicles — with police and city workers — to help evacuate people from their homes in East Nashville and the Jefferson Street area. This action saved lives, and there was only one known fatality from the flood.

Before television and the internet, the Nashville Real Estate Board provided a list of vacant homes where people could stay. Fifty individuals and businesses offered vacant homes or rooms where people could stay at no charge.

WLAC radio, which started broadcasting a month before the flood, immediately suspended regular programming to alert Nashvillians of the rising floodwaters. As floodwaters continued to rise and conditions worsened, WLAC started asking for money to help those in need and quickly raised $50,000 to aid those who were displaced.

After a devastating flood on Christmas Day in 1926, Nashville residents and organizations came together to raise funds and find shelter for those who were affected by the disaster. Image: Tennessee State Library and Archives

After the flood, Mayor Howse summed up Nashville’s response by saying, “The people of Nashville will respond speedily and generously,” and “Nashville always takes care of its own.” Nashvillians had donated so much money and help that Mayor Howse turned down offers of financial support from the federal government and the National Red Cross.

Music was also created as a response to the Christmas Day flood. Chattanooga-born blues singer Bessie Smith wrote a song called “Backwater Blues,” which was about the flood — “when it rained five days and the sky turned dark as night.” Bessie recorded the song six weeks after the flood, which became a big hit due to the 1927 flood of the Mississippi River.

2020: Tornado, Pandemic, Christmas Day Bombing

While there have been a handful of fairly significant Nashville disasters since 1926, 2020 has arguably been one of Nashville’s worst years. The lessons we learned from the unexpected disasters of the past are for Nashvillians to continue our generosity, unity and strength to rebuild. When our civic, political and business communities come together, all problems can be solved. The foundation of Nashville is as strong as the limestone we live on and cannot be destroyed by any fire, flood, pandemic, crash or bombing.

David Steele Ewing is a ninth-generation Nashvillian, historian, tour guide, and founder of the Instagram page @thenashvilleiwishiknew. You can also find him on Twitter @DavidSEwing

Source: StyleBluePrint