My ___ Was a Suffragist

By Jennifer Harlan

The New York Times

July 2, 2020

On Aug. 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment. Eight days later, ratification was certified by the secretary of state. The right to vote for women across the United States was officially enshrined in the Constitution.

The codification of suffrage was the result of nearly a century of activism, which began even before the Seneca Falls convention in 1848. From those early years to the formation of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890 to the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington in 1913, generations of American women and men devoted their lives to fighting for the vote. The movement was a decades-long game of democratic Telephone: Of the 68 women who gathered in that town in upstate New York and declared what was then a radical notion — that all men and women were created equal — only one, Charlotte Woodward Pierce, would live to see their dream become a reality.

And their struggle did not end with the amendment. Well after 1920, there were many women in the United States, including Native Americans and Chinese immigrants, who were not able to vote and many more, particularly African-Americans, for whom it was extremely difficult. One hundred years later, the country is continuing to grapple with many of the same questions the suffragists raised, not only who gets to vote but also what it means to be a citizen and how to ensure that all Americans are equal in the eyes of the law. And as we mark this centennial, the generation that came after the suffragists, and the ones that have come after that, are still in the fight.

“Learning your history is an essential tool, and a call to action,” said Liza Mickens, a great-great-granddaughter of the suffragist Maggie Lena Walker. “I’m honored to be a part of this legacy.” (Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.)

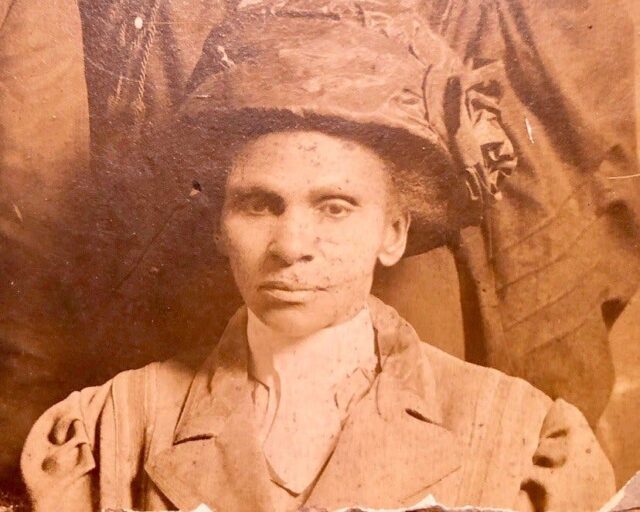

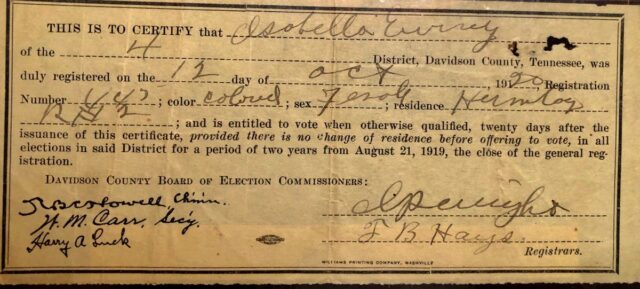

David Steele Ewing, 53, Nashville

Great-great-grandson of Isabella Ewing

My father died when I was 2 years old, so I grew up not knowing a lot about the Ewing family. But at a family reunion about 25 years ago, I kept hearing about Prince Albert Ewing and Isabella, my great-great-grandparents. It was a surprise to me to hear about people who I’m related to, who lived in the city where I’ve always lived and who were so involved in the Nashville African-American community.

This was before the days of online genealogy, so I did the old-fashioned work of going to courthouses and libraries to discover more information. They were both enslaved, Prince Albert at a place called Travellers Rest and Isabella at the Hermitage. They were married in 1871 and purchased some land near the Hermitage, where they built a house. That’s where I found their voting cards. Prince Albert was a magistrate in the 1880s. He was elected three times. But Isabella couldn’t vote for him. So it was very important, even though he was no longer on the bench, that she went to register as soon as she could.

There’s all this talk that women were “given” the right to vote. Women were not given the right to vote: They fought for the right to vote. They organized for the right to vote. They demanded the right to vote. This didn’t happen by magic. They really had to fight for it.

Source: The New York Times